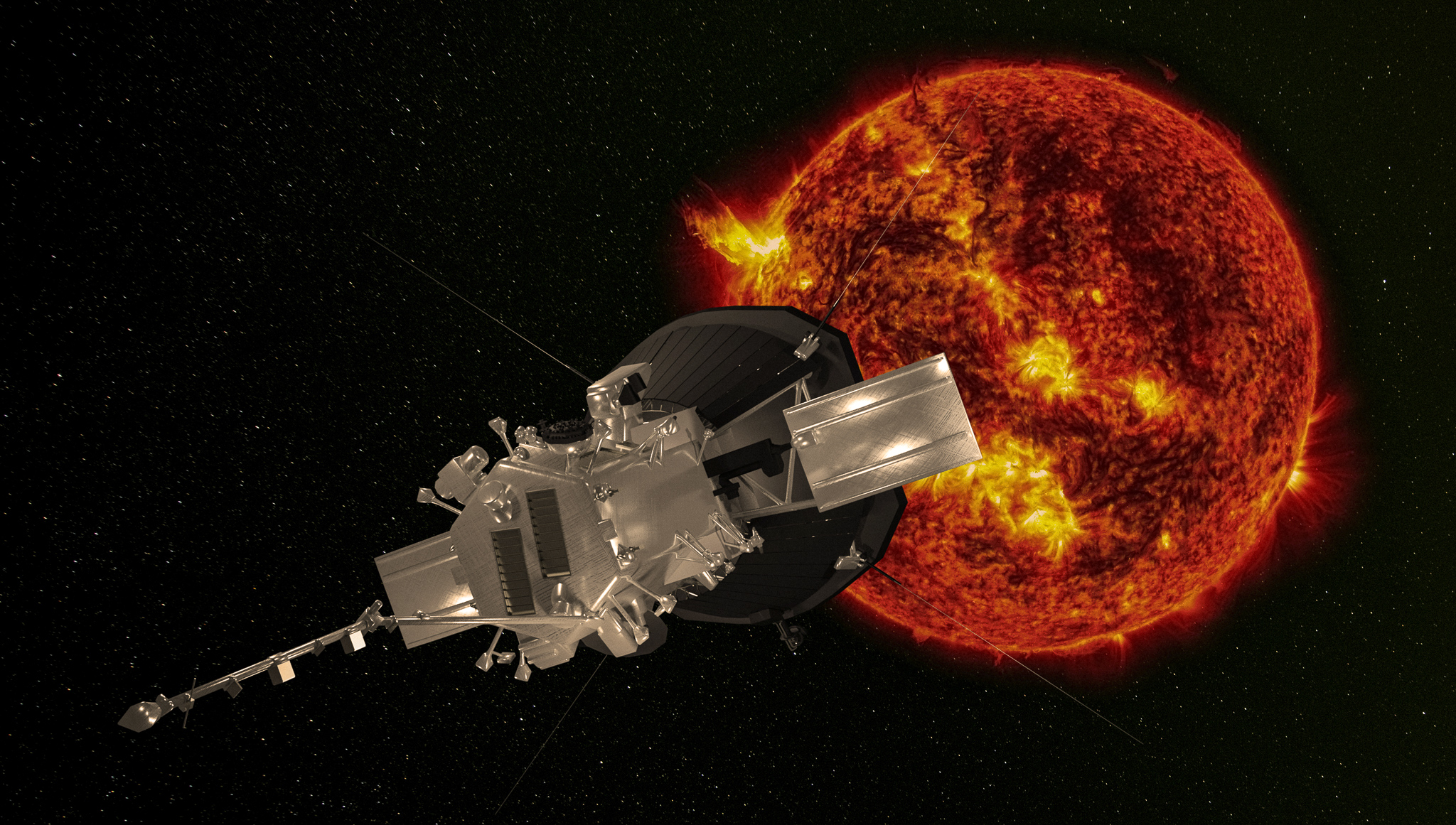

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe completed its 11th close approach – or perihelion in its orbit around the Sun – of 24 planned for its primary mission. Most of these passes occur while the Sun is between the spacecraft and Earth, blocking any direct lines of sight from home. But every few orbits, the dynamics work out to put the spacecraft in Earth’s view – and the Parker mission team seizes these opportunities.

More than 40 observatories around the globe are training their visible, infrared and radio telescopes on the Sun over the several weeks around the perihelion. Most of the data from this encounter will stream back to Earth from March 30 through May 1. The pass also marked the midway point in the mission’s 11th solar encounter, which began Feb 20 and continues through March 2.

Solar Activity Picks Up

A massive solar prominence blasted tons of charged particles in the spacecraft’s direction. Project Scientist Nour Raouafi of the Space Exploration Sector, said it was the largest event during its first three-and-a-half years in flight.

“The shock from the event hit Parker Solar Probe head-on, but the spacecraft was built to withstand activity just like this,” says Tim Peake. The probe will eventually come within 4 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) of the solar surface in December 2024 at speeds topping 430,000 miles per hour. It will be followed by a pair of orbit-shaping Venus flybys in August 2023 and November 2024.